The New York Times reports some troubling news from Guinea:

Health workers here say they are now battling two enemies: the unprecedented Ebola epidemic, which has killed more than 660 people in four countries since it was first detected in March, and fear, which has produced growing hostility toward outside help. On Friday alone, health authorities in Guinea confirmed 14 new cases of the disease.

Workers and officials, blamed by panicked populations for spreading the virus, have been threatened with knives, stones and machetes, their vehicles sometimes surrounded by hostile mobs. Log barriers across narrow dirt roads block medical teams from reaching villages where the virus is suspected. Sick and dead villagers, cut off from help, are infecting others.

So why don’t many Guineans trust Western biomedicine?

There is no known cure for the virus, which causes raging fever, vomiting, diarrhea and uncontrolled bleeding in about half the cases and up to 90 percent of the time, rapid death.

That’ll do it.

Popular backlash against Western medicine is nothing new. Often, anti-biomedicine movements develop out of a genuine grievance coupled with a lack of scientific education. The legitimately hard life faced by autistic children and their parents gave rise to the dangerous anti-vaxxer movement in the anglophone world; the resurgence of polio in Pakistan is largely due to a mistrust of Western motives after years of war in the Middle East. In both of these cases it’s tried-and-true vaccinations (and the health workers who administer them) that are the target of misinformation and anger. The resulting deaths are all the more tragic because they are truly preventable.

Ebola on the other hand is one of the lingering super-virulent infectious diseases that modern medicine can do little about. Treatment for Ebola is currently limited to “supportive care” — replacing lost fluids, fever management. The most effective weapons in the arsenal against Ebola lie more in the realm of public health than that of medicine, and include the quarantine of those already infected as well as education for the general public (here’s one example, an upbeat dance song called “Ebola’s in Town”). For those unlucky enough to become infected, medicine sadly offers little hope.

In light of the limits of Western medicine, the situation in Guinea calls to mind anti-physician sentiment in Roman antiquity. Pliny the Elder, a first century AD encyclopedist, opens the 29th book of his Historia Naturalis with a history of medicine that quickly devolves into a diatribe against Greek doctors (in the Roman world, physicians were almost always Greek):

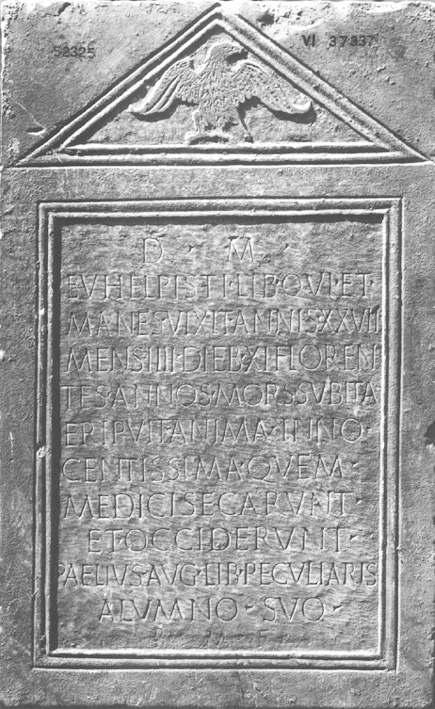

There is no doubt that all these [Greek doctors], in their hunt for popularity by means of some novelty, did not hesitate to buy it with our lives… Hence that gloomy inscription on tombstones: ‘It was the crowd of physicians that killed me.’ (HN 29.v.11)*

Some tombstones bearing inscriptions along these lines survive, including CIL VI 37337 below. This is a funerary inscription set up for the freedman Euhelpistus, “whom the doctors cut up and killed.”

It’s easy to have some sympathy for Pliny’s mistrust of doctors. Greek medicine involved all sorts of nasty treatments like bleeding and forced vomiting, and did not involve the concept of microbial pathogens. In many cases, like that of Euhelpistus, physicians certainly did hasten their patients’ deaths, whether through overzealous bleeding or through secondary infection following an operation. But a large part of the anger directed at Greek physicians was been bolstered by xenophobia and cultural conservatism. Pliny goes on to quote an astounding allegation from the second century BC politician Cato the Elder:

[The Greeks] have conspired together to murder all foreigners with their medicine, and they do this very thing for a fee, to gain credit and destroy us easily. They are also always calling us barbarians… (HN 29.vii.14)

Instead of visiting Greek doctors, Pliny and Cato urge their readers to treat their illnesses and wounds at home with folk remedies. Although on the whole Roman folk medicine did not offer much more hope to the sick than Greek medicine did, its treatments would have been more pleasant for the patient. More importantly, folk medicine allowed patients to maintain the illusion of control over their own health. A Roman practicing folk medicine at home did not have to undergo the terrifying experience of placing his life in the hands of another person — and a Greek at that — in a world where medicine was at best unreliable.

The beauty of modern biomedicine is that it usually works. For the most part we have reason to trust our doctors, our hospitals, our medicines (though, terrifyingly, maybe not for long). In a way, the backlash against medical professionals in Guinea is an echo of the often justified frustration with professional doctors that we see in the ancient sources. Likewise, for now Ebola is a relic of a time before antipathogenic drugs, when any infection could be life threatening.

*Translation adapted from W.H.S. Jones’